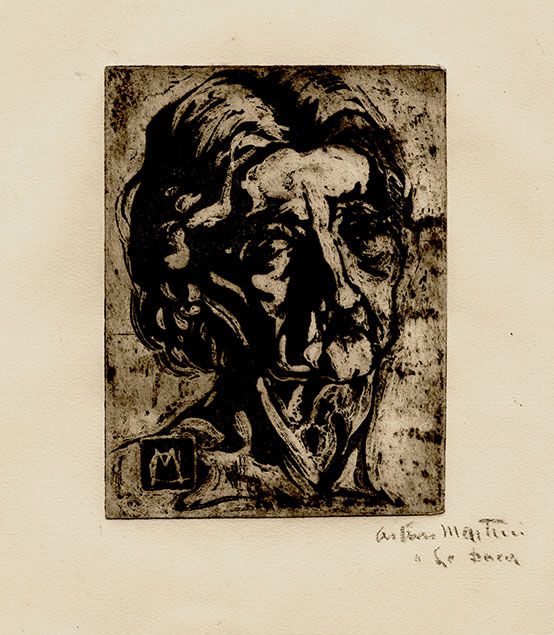

(Treviso 1889 - Milan 1947)

LA MADRE, 1915

Intaglio print, from a clay plaque. To the platemark 200 x 152 mm. Large margins.

Signed and dedicated in black chalk at bottom right Arturo Martini / a Lo Duca.

The dedicatee is Joseph-Marie Lo Duca, who published in Milan, in 1933, a book devoted the work of Martini.

PROVENANCE:

Libreria Prandi, Reggio Emilia, blind stamp at the bottom right corner. See their catalogue 200, 1989/1990, no. 446, illustrated.

The print is very rare, like all those obtained from delicate matrices in clay.

Another impression is in Treviso, at the Museo Civico Luigi Bailo. See Il Giovane Arturo Martini, opere dal 1905 al 1921, catalogue of the exhibition, Treviso 1989-90, cat. No. 107, illustrated.

Arturo Martini was the most important Italian sculptor of the first half of the 20th century. He was primarily a sculptor, but also painter and engraver. Raised in a modest and humble family, he was trained in goldsmithing and in ceramics and worked for a time as a potter. In 1905 he began sculpting; he attended art classes in Italy at Treviso and Venice before traveling to Munich, Germany, where he studied under the academic sculptor Adolf von Hildebrand in 1909. He first exhibited his sculptures in Paris in 1912. Martini worked with many materials (clay, wood, plaster, stone, especially marble, bronze, silver) but never moved far from figuration, although he was able to model abstract forms. Despite studying in Paris and Berlin, and his early support of Futurism, Martini’s works swing between aggressive modernism and classicism, but not toward avant-garde experimentalism, as was typical of the works of many prominent Italian artists during the Fascist Ventennio. Martini taught for a time at the Accademia di Belle Arti in Venice. Despite Martini’s doubts and dilemmas about sculpture, he expressed fruitful and innovative thoughts in the pamphlet Scultura Lingua Morta (the language of sculpture is dead), published in Venice in 1945.

As a printmaker Martini devised his own method of using terracotta, clay and gesso matrices for his prints. After baking the clay, he covered the incised surfaces with shellac, and used the bone handle of an umbrella to print his cheramografie. Martini also made woodcuts, linocuts and lithographs.